Seven Lessons From the German 5G Debate

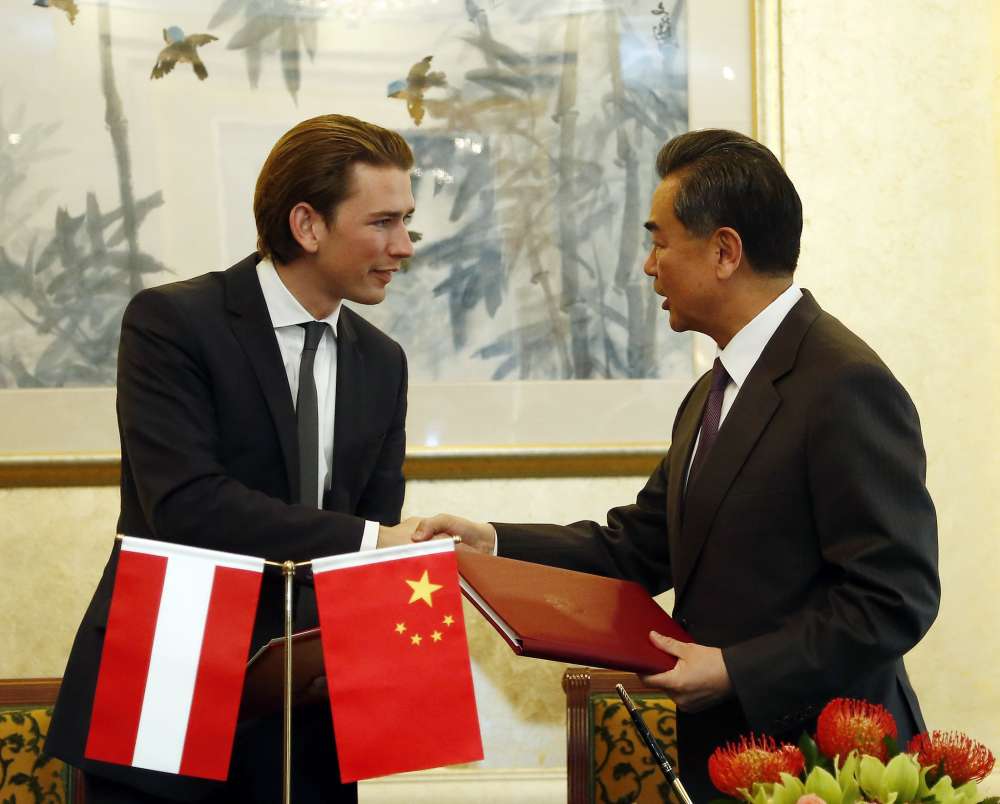

Three years ago, on December 1, 2018, Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s deputy board chair and chief financial officer, was arrested at Vancouver International Airport based on an extradition request by US authorities. The high-profile case of the daughter of Huawei’s founder Ren Zhengfei was the first time that major media confronted the German public with the fact that Germany’s mobile communications infrastructure to a significant degree relies on technology from Beijing’s global champion. This triggered an intense political debate on whether Germany should allow Huawei to be part of its 5G networks. This infrastructure for the next generation of mobile technology will be absolutely critical since it will enable the Internet of Things, including industrial production, driverless cars and remote health applications.

In the spring of 2021, after more than two years of political wrangling, the German parliament passed a new IT security law that defined the process for deciding which technology providers are to be entrusted with different parts of critical 5G infrastructure. One of the first tasks of the new German coalition government will be to apply the new rules and decide on whether German operators will continue to be allowed to rely on Huawei technology for their access networks. The main operators (Deutsche Telekom, Vodafone and Telefonica) have already decided to no longer use Huawei for their core networks. The increasing virtualization of 5G networks means the distinction between “smart” core servers and “dumb” access networks with just antennas no longer applies. It also means that access networks are becoming increasingly critical parts vulnerable to potential remote sabotage.

Since this will not be the last debate on the reliability of technology providers for critical infrastructure that Germany and Europe as a whole will face, it is useful to draw a number of key lessons from the German 5G debate.

Lesson 1: Be Prepared

The first lesson concerns preparedness. Germany was not ready for the 5G debate and thus unable to approach it holistically. Questions about the trustworthiness of suppliers beholden to Beijing should not have caught Berlin off guard. Australia conducted a debate on this matter already in 2018 and 2019 and decided to exclude high-risk suppliers from authoritarian states. And the US, Germany’s main security provider, very much pushed, under Trump, for US allies to carefully consider the risks incurred when relying on Chinese technology suppliers such as Huawei and ZTE. And yet few in the German government were prepared for dealing with this question, nor were their Chinese counterparts. In the late summer of 2019, Huawei representatives assumed that an Australiaמ-style debate on the exclusion of Huawei from 5G critical infrastructure on security grounds was not in the cards for Germany. Huawei officials were confident that their long-standing ties to Germany’s main three mobile operators and their track record of offering excellent value for money and being a reliable partner would shield them from closer scrutiny. After all, Deutsche Telekom and others had clearly signaled their intent to move ahead with Huawei technology as a key element of their 5G networks. Therefore, it seemed inconceivable to key decision-makers in both the public and private sectors that the simple question “Can we allow our 5G critical infrastructure to be built with technology provided by a company that is private on paper but ultimately answerable to the Chinese communist party state?” would resonate with the German public once asked forcefully.

The price paid for this lack of preparedness all around was the neglect of vital considerations not involving security, such as the breadth of coverage and rollout speed. When the issue of Huawei’s trustworthiness eventually did hit Germany, the security aspect dominated the discussion on building the next-generation mobile networks, at the expense of other considerations. There was no effort to look at the issue of building the best possible networks from a holistic perspective. This should have been simple. Early on in the debate, there should have been a competition of ideas as to how to best combine the goals of building the most trustworthy and secure network with the broadest coverage possible beyond dense urban areas and fast rollout. Instead, Germany discussed the security aspect – but not in conjunction with other aspects. Early on, policymakers agreed to rely on spectrum auctions for the sale of 5G airwave licenses to the highest bidder to squeeze the maximum out of operators, and only later began delving into the question of how to build the most secure and capable networks. It was only with the advent of the new coalition government in November 2021 that Germany is now considering burying spectrum auctions for the 800 MHz frequency crucial for coverage in rural areas. The coalition treaty talks about negative auctions that would award licenses to those who need the lowest amount of subsidies for optimal coverage in rural areas where offering fast connections is not profitable. Here, Germany should have learned from China, where the government does not auction off spectrum but rather awards contracts based on coverage goals.

Lesson 2: Support All European Technology

Second, German politicians talk a good game about EU-wide industrial policy to ensure “European technological sovereignty.” They claim to care about Europe’s ability to master critical technologies. But if no German company has skin in the game, German politicians do not tend to be too concerned about the fate of European technology companies. This was particularly striking to watch in the 5G debate. Mobile technology is a peculiar field. Unlike most other advanced technologies, none of the current 5G market leaders is from the US. Rather, Huawei’s biggest and most capable competitors are two European companies, Ericsson and Nokia. Their Swedish and Finnish governments tend to be quite weak at supporting them, given that they still harbor quite a few illusions about open and fair competition. But that open and fair competition is no longer a reality in today’s global economic system where companies such as Huawei profit from the advantage of being the darlings of Beijing’s authoritarian state capitalism. France and Germany tend to do more for their own companies given they have fewer illusions about fairness in the global marketplace. Had Ericsson and Nokia been Alcatel and Siemens, you can be sure that Paris and Berlin would have sprung into action full force to support their champions. But they barely lifted a finger for Swedish and Finnish companies. A comment by Bavarian Prime Minister Markus Söder in early 2020 gave this away. Söder argued in an interview with Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung that “the current debate on Huawei and 5G demonstrates how serious things have become. In the old days it would have been clear that Germany takes a Siemens network. Now we have to decide between difficult alternatives. We need our own competency.” This is a revealing statement on many counts. The “our own” is purely German. European competency does not count. In a rather peculiar twist, Söder characterizes the choice between two European companies and a Chinese company as a decision between “difficult alternatives.” This demonstrates that too many German decision-makers have a parochial mindset when it comes to European technological sovereignty. Any technology that is not German does not really count. But German decision-makers talking about Europe’s competitiveness in their Sunday speeches should have an interest in strengthening European rather than purely national champions.

Lesson 3: Ensure an Independent German and European Debate

Third, interventions by the US government into the German debate proved mostly counterproductive. The Trump administration tried to pressure the German government into excluding Huawei, including by threatening to cut Germany off from intelligence sharing. This had the effect of shifting the debate’s focus to Germany choosing between China and a deeply unpopular US president. After all, while Germany was facing a choice between European and Chinese companies and not between US and Chinese companies, the strong interventions by the US government led many among the German public to believe that the choice was between the US and China. This weakened the position of those arguing in favor of excluding high-risk providers such as Huawei on European national security grounds. Also, decision-makers in the Trump administration did not quite appreciate that US-generated terms like “clean network initiative” (for Huawei-free networks that protect against Chinese espionage) did not help the case against Huawei in Germany. Many Germans readily associate the US with espionage based on the discussion about files leaked by Edward Snowden on NSA surveillance. It would have been smarter for the US to leave the discussion to Germans and Europeans, restricting its own role to providing credible supplementary evidence on the sabotage risks incurred by relying on Huawei and other high-risk Chinese providers. Europe is very much capable of doing its own risk assessment, as evidenced by the EU’s quick publication of the toolbox on secure 5G networks in early 2020.

Lesson 4: Limit Misinformation

Fourth, misinformation, advanced by both experts and lobbyists, was rampant during the debate. On the part of experts, this may not have been on purpose but was rather based on a lack of knowledge. Take the example of Christoph Meinel, head of the Hasso Plattner Institute and one of Germany’s highest paid professors of information technology. In late 2019, Meinel claimed that Huawei and Cisco were world market leaders in 5G and that there were no European competitors worth the mention. He argued that the goal of the US government was to ensure that Germany buys US products for its 5G critical infrastructure (instead of Chinese products). This, of course, was spectacularly wrong. Nokia and Ericsson are the two main competitors of Huawei. And the choice for Germany and Europe is chiefly between European and Chinese suppliers. The Trump administration’s heavy-handed push against Huawei at the time mostly benefitted European, not US companies. Meinel’s spreading of misinformation may not have been intentional. But the major operators’ lobbying on behalf of Huawei did amount to intentionally spreading misinformation. Deutsche Telekom, Telefonica and Vodafone all played a harmful role in the 5G security discussion, spinning it in favor of Huawei and spreading outright disinformation. This includes unfounded assertions that major delays were to be expected should Huawei be excluded from building 5G networks. One of the wildest examples of disinformation is the letter Telefonica sent to German members of parliament (MPs) in November 2019. The letter claimed that Huawei was the leader in price and quality, and that its hardware was more energy efficient than that of its competitors. It also claimed Europe had largely lost its production expertise in mobile network hardware. Telefonica also asserted that a Huawei ban would hurt German economic interests and set the country back by several years. In her tireless fight on behalf of Huawei, Deutsche Telekom Board Member Claudia Nemat also warned of “years of delays” and “many billions of additional costs.” A number of telecom industry representatives also raised doubts about Nokia’s and Ericsson’s ability to deliver at an adequate pace and in sufficient quantity in case Europe chose to rely on them for 5G networks, whereas the concern should have been with Huawei having its own ability to deliver hampered by US sanctions. All too often, the German media uncritically relayed misinformation spread by telecom operators.

Lesson 5: Shun the Fear of Retribution

A number of German decision-makers were paralyzed by fear of retribution against German companies on the Chinese market and therefore decided to forego Germany’s national security interest. The Chinese party state cleverly exploited these fears. Wu Ken, China’s ambassador to Germany, at an event in Berlin that discussed Huawei and 5G in December 2019, said something that amounted to a mafia-style threat: “Nice car industry you have there. Too bad if something happened to its sales in China.” The Chancellery, the Ministry of the Economy and at times also the Ministry of the Interior understood the message and tried to push ahead with their open-door policy for Huawei against mounting resistance from across the political spectrum. In theory, then-German Interior Minister Horst Seehofer was vested with safeguarding the safety and security of German citizens. But in the discussion on 5G security, he often decided to side with Huawei, based on fears of retribution against Audi, a major company in his home region with vested interests in the Chinese market.

Then-German Economy Minister Peter Altmaier even resorted to an absurd analogy when discussing the possible exclusion of Huawei from 5G critical infrastructure. At an event organized by the Munich Security Conference in late 2019, he argued that if Germany were to say that it does not trust Huawei, “what will happen if other countries say ‘I don’t trust French wine’.” The analogy is, of course, absurd. Wine is not exactly critical infrastructure and it does not make any sense to lump it together with mobile networks. But in his quest to justify Huawei’s inclusion, Altmaier was not choosy with his arguments. Rather than allowing a fear of retribution against German companies selling non-critical infrastructure in China to dictate the discussion, German and other European decision-makers should have clearly articulated that they would fully understand if China decided to exclude European suppliers such as Nokia and Ericsson from 5G critical infrastructure. For years, both companies were allowed a small slice of the Chinese market that is dominated by Chinese providers such as Huawei and ZTE. Given the size of the Chinese market, even that small slice was significant for Ericsson and Nokia in terms of global turnover. It was a mistake, though, for both companies to try to cling to the Chinese market when at the same time Sweden had decided to exclude Huawei from its 5G networks. The consistent position would have been to accept that both companies do not have a future on the Chinese market, rather than lobbying for continued inclusion.

For the future, the new German government should self-confidently apply the regulation of the new IT security law and make sure non-trustworthy suppliers such as Huawei that are beholden to non-democratic governments are excluded from developing critical 5G infrastructure. And at the same time, the new government should send a signal to German companies such as Volkswagen and Daimler that have chosen to make themselves highly dependent on sales in the Chinese market: “You do so at your own risk. We will not conduct our China policy and compromise key strategic interests based on a fear of retribution against German companies.”

Lesson 6: Support Smart Policy on Open RAN

Germany is not yet properly prepared to pursue its industrial policy goals with a view to future mobile technology developments such as 6G. One illustration of this is Germany’s approach to Open RAN. The German government (through research funding, public statements) has thrown its weight behind Open RAN in recent years. But it has done so in a way that is very different from the US government. The US is pushing Open RAN as a means of ensuring that the future of mobile technology will be dominated by US companies. This is the US response to the rude awakening it received when it realized that 5G is one of the few high-tech areas where the US does not have a leading global company that offers the full technology spectrum. US company Mavenir clearly stated that it is pushing Open RAN in order to create “a more robust mobile ecosystem where U.S.-headquartered companies lead the world in 5G.”

So far, Germany has naively supported this push with German taxpayer money. Contrary to the US, which supports its own companies, Germany does not prioritize the support of European companies and a European-led ecosystem. But it has allowed public subsidies and research support to go to US companies. An alternative would have been to strengthen innovative European companies in the mobile technology space. But in its Open RAN pilot network, Deutsche Telekom, for example, relies mostly on companies from outside Europe, while US think tanks such as the Center for New American Security sell Open RAN as Europe’s “bulwark against Chinese economic coercion.” This is beyond parody given that China Mobile is a founding member of the O‑RAN Alliance and that other Chinese companies play a leading role there.

Lesson 7: Appreciate the Difference Parliaments Can Make

The 5G debate demonstrates the key role that parliaments can play and that political entrepreneurship pays off. The Chancellery and Angela Merkel personally invested a lot of political capital pushing for a Huawei open-door policy on 5G. In the end, Merkel had to bow to parliamentary opposition to her stance within her own party, her coalition partner SPD as well as the Greens and the FDP. That was a big victory for the Bundestag, Germany’s parliament. Within Merkel’s CDU party, Norbert Röttgen, the chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee, led the charge against allowing Huawei to build Germany’s 5G infrastructure. A number of political entrepreneurs within the Social Democratic parliamentary group banded together to write a path-breaking position paper on Chinese policy that provided the backdrop for the SPD pushing for a more security-minded stance on 5G, even as the SPD prime minister of Lower Saxony (the German stat that is home to Volkswagen) advocated in favor of Huawei. SPD MPs also worked together with the SPD-led Foreign Office, which advocated in favor of excluding non-trustworthy suppliers from critical infrastructure. MPs from both the Greens and the FDP were also instrumental in the parliament’s push against Merkel’s open-door policy on Huawei – through parliamentary hearings and work on the revised IT security law.

That parliamentarians managed to assert themselves against pro-Huawei lobbyists as well as the parts of the executive branch working in favor of non-trustworthy suppliers is the most uplifting part of the German 5G saga. On the road ahead, parliament can also work to ensure that Germany learns the other key lessons from the sometimes painstaking process of finding the best path for moving ahead with 5G critical infrastructure.

This article was originally published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation and Israel Public Policy Institute on December 30, 2021.