Iraq after ISIL: Tuz

PMF and Kurdish forces are locked in a stalemate in Salah ad-Din’s only Disputed Territory. Still under split control two years after ISIL’s ouster, the district capital is divided, while local Shi’a militias prevent Sunni Arabs and Sunni Turkmen from returning to their homes in their southern area of control.

This research summary GPPi is part of a larger study on local, hybrid and sub-state security forces in Iraq (LHSFs). Please see the main page for more findings, and research summaries about other field research sites.

Saddam Hussein carved Tuz district off from oil-rich Kirkuk governorate in 1976 to undercut Kurdish aspirations for autonomy. Since then, it has formally been part of Salah ad-Din; however, with its location on the border of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and its multi-ethnic make-up (split almost evenly among Turkmens, Kurds, and Sunni Arabs), Tuz has political and conflict dynamics more similar to those in neighboring Kirkuk governorate than to the rest of Salah ad-Din governorate. It is the only part of Salah ad-Din that would be subject to an Article 140 referendum and as a result, the post-2014 period has witnessed efforts to politically gerrymander Tuz by changing control on the ground, which has also been taking place in Kirkuk and other Disputed Territories.

During the period of research, Tuz was at the center of an active contest for power by different LHSF groups, both national and local, which created significant consequences for the populations aligned with these different groups. The central government was virtually absent from the district until May 2017 and subsequently was restricted to one of the three sub-districts, Amerli. Since the ouster of ISIL at the end of 2014, the other parts of Tuz have been under split PMF and Peshmerga control, with the different forces’ lines of control and presence varying over time. PUK-affiliated Kurdish Security Forces have been dominant in the northern parts of the central sub-district, including parts of the district’s capital, Tuz Khurmatu. A range of Shi’a PMF forces (primarily Badr but also the Peace Brigades, Hezbollah Brigades, League of the Righteous, and others) control the rest of the district via local PMF franchises mobilized among the Shi’a Turkmen population.

Key Facts: Tuz

Population: 180,000-200,000

Ethnic Composition: Sunni Arabs, Kurds, and Turkmen (Shi’a and Sunni)

Date taken by ISIL: June 2014

Date reclaimed: August-October 2014

Forces engaged: PMF, Peshmerga, Coalition and Iraqi air support, volunteers

Overall Control: Split control between Peshmerga and PMF

LHSFs present: PUK Peshmerga; local Turkmen PMF (affiliates of Badr, Peace Brigades, Hezbollah Brigades and League of the Righteous); Khorasani Brigades and Imam Ali Combat Division also present

Key Issues:

- Divided Kurdish and Turkish control, periodic conflict, unresolved through mediation

- Continued ISIL threat

- No return of Arabs and rights violations in PMF-controlled areas

The different LHSF factions’ efforts to control particular areas and protect the constituents affiliated with them have had a direct effect on the safety and return of competing ethnic or sectarian groups. Sunni Arab residents of Amerli sub-district, Suleiman Bek sub-district, and the rural areas of the central sub-district could not return to their homes to this day due to large-scale destruction of property by the PMF and Kurdish Security Forces and/or fear of retaliation by Turkmen PMFs. Rights violations against Sunni Arabs are ongoing in Tuz Khurmatu city’s mixed-community neighborhoods, where local PMFs are in control.

Tuz is one of the areas in Iraq (in addition to parts of Diyala) where Kurdish security forces have clashed with the Popular Mobilization Forces. Although the lines of control are clear outside the district’s capital, Tuz Khurmatu city remains a throbbing flashpoint because both the Kurdish and Turkmen communities claim control over it. The top Shi’a cleric in Iraq, Ali al-Sistani, stepped in to negotiate a cease-fire among different sides in March 2016, but several commitments were not implemented, which led to a breakdown in trust. More recent reconciliation efforts have not been fruitful. Given the continued ISIL security threat from nearby Hawija, in Kirkuk governorate, the demilitarization of the Shi’a Turkmen and Kurdish communities is unlikely. So long as they remain mobilized and in control, they are likely to continue to compete for primacy in Tuz Khurmatu, meaning that the current dynamics are likely to persist.

Background and Pre-ISIL Dynamics

Tuz Khurmatu – Tuz district’s capital – is a multi-ethnic city on the historic trade route between Baghdad and Kirkuk. Although Tuz is historically part of Kirkuk, the entire district was administratively separated from oil-rich Kirkuk governorate in 1976, as noted, to decrease the share of Kurds in Kirkuk. Entire villages (primarily Kurdish) were razed, and many were killed under Saddam Hussein’s rule, including during the Anfal in 19882 and the Baathist reprisal against the 1991 uprising of Kurds in northern Iraq.3

Tuz is the only district in Salah adDin governorate subject to an eventual referendum under the provisions of Iraqi Constitution Article 140.4 Tuzdistrict has a population of about 180,000−200,000 people, split almost evenly into three constituencies: Sunni Kurds, Sunni Arabs, and Turkmens, who are predominantly Shi’a Muslim with pockets of Sunni Turkmens.5

Since 2003, the allocation of seats has followed an ethnic power-sharing arrangement: seven seats of the district council are assigned to Kurds, seven to Arabs, and seven to Turkmens. Additionally, the head of the district council is a Sunni Arab, its deputy is a Turkmen, and the secretary-general is a Kurd. The district council has elected a Kurdish mayor since 2003.

The demographics for the respective areas are as follows:

Central District

- Population: 80,000−100,000

- Demographic composition (majority): Tuz Khurmatu city (Shi’a Turkmen and Kurdish), Yengice town (Sunni Turkmen), seven Arab villages, one-two Kurdish villages

Amerli6

- Population: ca. 70,000

- Demographic composition (majority): Amerli town (Shi’a Turkmen), 40 Arab villages, three Shi’a Turkmen villages

Suleiman Bek

- Population: ca. 30,000

- Demographic composition (majority): Suleiman Bek town (Arab) and 10 Arab villages

As part of Iraq’s Disputed Territories, Tuz district has been controlled jointly by the KRG and GOI Security Forces since 2003. Mistrust between the parties resulted in weak control (and, on occasion, open confrontation).7 Explosions rocked the district on an almost daily basis from 2011 to 2014. Much of the violence predominantly affected Shi’a Turkmen neighborhoods, causing an estimated 2,000−3,000 casualties according to a Turkmen community representative. However, it also affected other areas and public officials of all ethnicities were also increasingly targeted. The neo-Baathist Army of the Men of the Naqshbandi Order (JRTN) staged four uprisings in predominantly Sunni Arab Suleiman Bek in 2013 – 2014,8 taking advantage of growing hostility to the government’s hard-handed counter-terrorism measures and the perceived marginalization of the Sunni community in Iraq. Neither Iraqi nor Kurdish Security Forces took effective steps to stop the spiraling sectarian violence and punish perpetrators, which frustrated members of the community.9 A government representative from Suleiman Bek exclaimed, “On 22 May 2014, ISIL bombed 20 houses in Suleiman Bek, including mine. It takes time to destroy 20 houses. I don’t understand why no one was captured. That house was the work of my life!”

ISIL Capture and a Strong PMF-led Response

Shortly after the fall of Mosul in June 2014, radical elements in Tuz took up arms and declared allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. In a matter of days, ISIL had taken control of almost the entire district, having faced little armed resistance. The Iraqi army (16th Brigade) had virtually disappeared, with no one reporting to duty. According to some locals, all military equipment at the Sadiq Airbase was consequently appropriated by KRG Security Forces. Furthermore, the federal police (7th Emergency Force) abandoned their base in Bir Ahmed, and the local police suspended its activities.

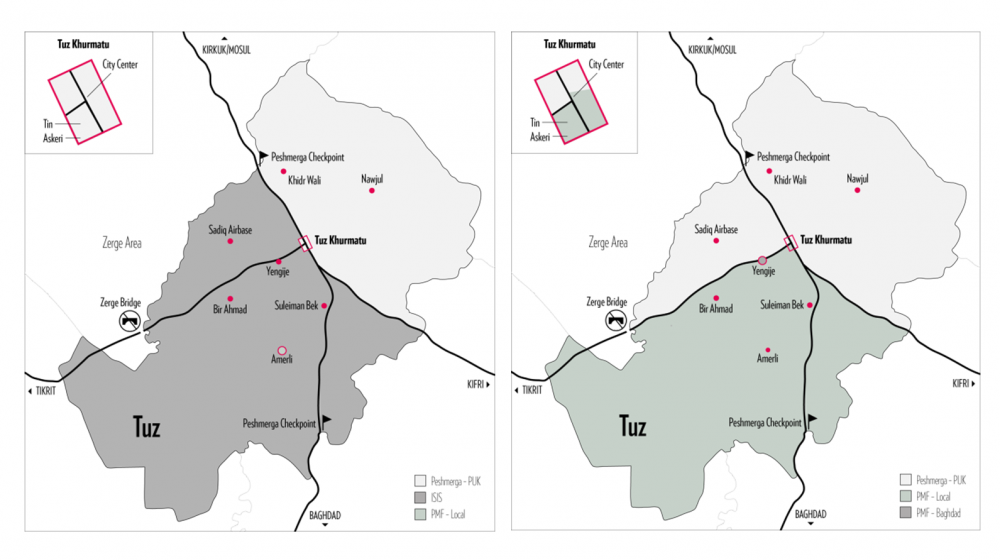

Only Tuz Khurmatu city and Amerli town escaped ISIL control (Illustration 1). The Peshmerga defended Tuz Khurmatu against ISIL, with support from local volunteers mobilized by Kurdish tribal elders and political parties (and unconfirmed mobilization by Shi’a Turkmen), and the Asayish – a Kurdish security force akin to police – conducted sweep searches to identify ISIL cells in the city.

In June 2014, ISIL surrounded Amerli town and cut off electricity, food, and water supplies. The imminent humanitarian disaster in the Shi’a Turkmen town prompted a strong response from national Shi’a PMF contingents. The Khorasani Brigades immediately dispatched fighters, followed by other PMF units, including the Badr Brigades, Hezbollah Brigades, League of the Righteous, Peace Brigades, Imam Ali Brigades, Risaliyyoun [kata’ib al-tayyar al-risali], and the Master of Martyrs Brigade [kata’ib sayyid al-shuhada].10 Under the tactical leadership of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, Quds Force Commander Qassem Suleimani, and Badr Commander Hadi al-Ameri, the assembled PMF forces broke Amerli’s 80-day siege on August 22, 2014 and cleared neighboring villages with support from Coalition and GOI air strikes,11 Peshmerga artillery, federal police units, and local volunteers.

ISIL was ousted from Suleiman Bek sub-district similarly, albeit with relatively greater involvement of Kurdish Security Forces in Suleiman Bek town. In the central sub-district, KRG-SF cleared areas north of theTuz-Tikrit road, while PMF-led forces focused on the villages south of it. The district was announced as “liberated” in October 2014 when ISIL combatants fell back toward Hawija (in Kirkuk) and blew up the Zerge Bridge in retreat.

According to some estimates, 200 people have died at the hands ofISIL or as a result of military operations since June 2014, and dozensare still reported missing.12 ISIL’s rule also prompted mass displacement from areas the group controlled. One local official estimated that only 25 – 30 percent of the population remained in Suleiman Bek sub-district after ISIL took charge: typically those who were either affiliated with ISIL or did not have the means to flee. Other tracking by international humanitarian monitors suggested three waves of displacement: 20 percent of the population fled in the first 10 days of ISIL control, and by June 28, 2014, 60 percent had moved to other areas. By the final month of ISIL control, almost no one was left but ISIL fighters. During the intense military operations to oust ISIL from June through October 2014, which included waves of massive shelling and aerial bombing, all civilians fled from ISIL-controlled areas. A local NGO, the National Institute for Human Rights, estimates the overall damage to physical property in the district at $30 million.13

Contests for Control

What has emerged in the aftermath of ISIL’s ouster is one of the starkest examples of LHSF contests for control, pitting local proxies and communities allied with Kurdish forces against those supported by the (Baghdad-affiliated) Shi’a PMF forces. The line of control is split,with active control usually depending on which forces cleared an area. Peshmerga forces control the northern half of the district that they liberated, while Shi’a PMF control the southern half, including Amerli and Suleiman Bek. The capital city of Tuz Khurmatu, which was taken by Peshmerga, straddles the dividing line between PMF and Kurdish forces inthe current lines of control. The city today is physically divided, with fortifications, concrete barriers, and checkpoints to cross as one passes from a Kurdish to a Turkmen neighborhood.

Other government forces in the district are either absent or too weakto attempt to challenge these actors or mitigate the stand-off between

them. Although the Iraqi Security Forces are technically present, they play virtually no role today in Tuz. When asked about Baghdad, all consulted stakeholders, regardless of creed or ethnicity, responded sternly, “The government?! The government is gone.” The local police wasunanimously described as woefully weak. Although the police undertakes routine tasks, such as securing government buildings and patrols, it is often accompanied by Turkmen PMF or Asayish, depending on the place of duty. The following testimony by a resident in Tuz Khurmatu’s Tin neighborhood highlights the imbalance in power between the local police and the PMF:

“In December 2015, a militiaman broke into a Sunni Arab shop in myneighborhood. The shopkeepers wrestled him down and called the police. Shortly after the police arrived, members of the League of the Righteousappeared and took the robber – he was probably one of their own. The police could not do anything.”

Besides the local police, the federal police (7th Emergency Force) are present, but not a single consulted informant could describe their current function. The Iraqi army’s 16th Brigade virtually disappeared after ISIL took parts of the district in June 2014, but the second commando regiment of the Northern Tigris Operations Command was restored to Amerli in May 2017, marking an important change in the presence of Iraqi Security Forces.14

Intra-PMF Coordination and Command

The PMF-controlled part of Tuz is in itself an interesting case study of command and cooperation among different groups under the PMF umbrella. While Badr is dominant in PMF-controlled Tuz, there is an amazing variety of PMF groups present. In Tuz Khurmatu, an unpaved street in the city center features the local headquarters of the official PMF command, Peace Brigades, Hezbollah Brigades, and – after a turn – the League of the Righteous. All local PMF forces in Tuz district formally belong to the PMF’s “northern front” operations, headquartered in Tuz Khurmatu, which handle coordination, logistics and pay. Local circumstances and the need to deal with local challenges give PMF commanders greater discretion over some local matters. Abu Ali, the head of League of the Righteous in Tuz explained, “Tuz is a volatile area; this grants me greater autonomy than brigade commanders in more-secure districts.”

The PMF headquarters helps mediate in the event of occasional “misunderstandings” between the groups. However, in the event of sensitive and potentially far-reaching issues – for example, new operations against ISIL, confrontation with Kurdish Security Forces, or return of IDPs – local PMF commanders must report directly to the PMF’s top commander, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis and to their own national-level leadership (e.g., Turkmen Badr commander reporting to Hadi al-Ameri). Although each group flies its own flag, all four of the consulted PMF representatives claimed intra-PMF relations were good and stressed they would immediately close ranks in case of an outside threat, “because [they] follow the same sect.”

PMF-controlled (Southern) Tuz

PMF-led operations to liberate Amerli and Suleiman Bek sub-districts were made possible by a pact between the KRG and Baghdad, which allowed free passage of PMF fighters to Tuz district via Kurdish-controlled areas in the north, on the condition that Shi’a Arab PMF forces would leave Tuz following ISIL’s expulsion. Accordingly, all southern PMF fighters left Tuz in December 2014 with the exception of the Khorasani Brigades, which remains in Yengice town to date.15 However, these national PMF groups kept a foothold in the Amerli and Suleiman Bek sub-districts via the mobilization of franchise groups, recruited from the local Shi’a Turkmen PMF population, following a call to arms by the PMF’s top commander, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, in September 2014. By the end of the year, the new local units had organized themselves under the banners of the different PMF forces to which they had prior connections or that had liberated the areas initially.16

At the time of research, these local, predominantly Shi’a Turkmen PMF units broadly controlled the southern half of Tuz district – including the PMF-liberated areas of Suleiman Bek and Amerli, up to and including part of Tuz Khurmatu. Although PMFs did not formally participate in defending Tuz Khurmatu, these local Turkmen PMF forces began establishing checkpoints there in December 2014, shortly after ISIL’s ouster. This move created a de facto area of PMF control within what had been an exclusively Kurdish-controlled area since the Iraqi army’s collapse in June 2014. The PMF areas of control in Tuz Khurmatu include the city’s Shi’a Turkmen neighborhoods (including the historic city center) and two mixed-community neighborhoods south of the Tuz-Tikrit road, Tin and Askeri (Illustration 2).

As they existed at the time of research, Turkmen PMFs fell under two brigades: Brigade 16, which is active in Tuz Khurmatu city, and Brigade 52, which conducts operations in Suleiman Bek and Amerli sub-districts and the border regions of Tuz, including Diyala and Kirkuk governorates. Each brigade includes a small Sunni Arab unit.17

Outside Tuz Khurmatu city, control is geographically split between a broad variety of PMFs, whose local commanders and rank and file are Shi’a Turkmen. Badr had exclusive control over Suleiman Bek sub-district. The Hezbollah Brigades and Badr were the main actors in Amerli sub-district (although Peace Brigades fighters were manning all three checkpoints on the way to Brawchili village in February 2017). The Khorasani Brigades – a PMF with predominantly non-local, Shi’a Arab members – were directly controlling Yengice town at the time of writing. One exception to this pattern of control is the League of the Righteous, which never attempted to hold territory in Tuz; however, at the time of writing, it still had combat forces engaged in operations (including detentions) in and around the district.18

“Tuz is safer than ever” is an oft-repeated phrase in PMF-controlled areas, reflecting significant security improvements since late 2014, at least for Shi’a Turkmen. According to Tuz General Hospital’s records, there have been 65 casualties from IED explosions in 2016 (including 13 fatalities),19 one-tenth of the average number of casualties in the 2011 – 2014 period.

However, while the southern half of Tuz may be safer for Shi’a Turkmen, it is the opposite for other ethnic and sectarian communities who once lived there. All other ethnic and sectarian communities interviewed pointed to systematic rights violations committed by Turkmen PMFs wherever they are in control. In Tuz Khurmatu’s mixed-community neighborhoods, Tin and Askeri, locals recounted daily abuse against Sunni Arabs by the PMF. This included targeted killings and abductions, which prompted the mass displacement of Arab residents (and Kurds, though their numbers were relatively small) to Kurdish-controlled areas of the city. According to interviewee estimates, only about 400 – 600 people, or 5 – 10 percent of residents, remain in the two neighborhoods because they lack the means to leave or are afraid to leave their property behind. The same interviewees reported abductions of Kurds (and to a lesser extent Sunni Arab members of the PMF) by Turkmen PMFs on the Tuz-Baghdad highway.

Membership and Pay

Initially, national PMF groups recruited local PMF subsidiaries in the areas they liberated or controlled. However, each PMF group has a specific allocation of fighters paid by the central government, and each group has now filled its registry. As a result, new volunteers can only be formally added (and paid) if someone drops off the list (e.g., killed in combat). Both Badr and the League of the Righteous claimed that voluntary donations supplement the 500,000 IQD per month salary provided by the central government. This has allowed them to pay more decent wages to their members. They did not confirm or deny whether the financial contributions come only from locals or include regional powers, such as Iran, but a few Turkmen leaders are known to have personal relationships with Quds Force Commander Qassem Suleimani.

According to a list compiled by a Kurdish local researcher working on this issue, whom the author saw but whose validity could not be confirmed, there were 153 cases of abductions and killings from December 2014 to February 2017 that targeted the Arab community in Tuz Khurmatu. Arab informants from Tin neighborhood suggested the total number is closer to 300. No matter the statistics, all interviewed Kurds and Arabs claimed they feared crossing into PMF-controlled parts of Tuz Khurmatu city and beyond. Several Kurdish interviewees claimed that the PMF and ordinary Shi’a Turkmen citizens have abused Kurds in the city’s main market and told them not to return.

This pattern of targeted attacks against Sunni Arabs was confirmed by Turkmen community representatives. However, the Turkmen PMF leaders consulted for this report only admitted to sporadic acts of criminality in the areas their forces controlled. For example, the head of the League of Righteous, which was named by Kurdish officials as the main perpetrator of related kidnappings and killings, denied these allegations and claimed, “[those] were committed by Sunni Arabs dressed in PMF uniforms.” When asked why all witnesses describe the perpetrators as Turkmen, he added, unconvincingly, “Some Arabs speak Turkmen, Kurdish, and Arabic fluently.”

There are also reports of retaliatory acts perpetrated by Turkmen PMFs. On October 22, 2015, a car explosion killed at least two people in Tuz Khurmatu. In response, Turkmen PMF detained at least 150 Sunni Arab residents, many of whom were killed and tortured, according to Human Rights Watch.20 In a notable attack on June 16, 2016, ISIL carried out a night raid against a number of security checkpoints and police stations in Amerli sub-district, killing Colonel Mustafa Hassan, head of Tuz district’s local police and commander of the 7th Emergency Battalion, among others.21 In the next two to three days, several reports described retaliatory executions of up to 52 Sunni Arab inmates in Amerli prison by Turkmen Shi’a militias.22

Similar to Arabs, Tuz district’s Sunni Turkmen community has suffered under PMF control. The head of the Turkmen Front, a Turkmen-nationalist political party with close ties to Turkey, explained that a car explosion in October 2014 prompted mass arrests and the displacement of practically all Sunni Turkmens from PMF- to Kurdish-controlled areas in Kirkuk and Tuz Khurmatu city. He added, “It is shameful that the Iraqi air forces bombed Sunni Turkmen villages, such as Yengice and Bartabli, as if they were ISIL.” A key informant claimed that targeted assassinations against members of the Turkmen Front and known figures who favor Turkey over Iran are still ongoing, which explains the presence of heavily armed body guards seen at the party’s headquarters in Tuz Khurmatu’s city center in February 2017. The local party leader concluded in despair, “The Turkmen community is shattered and divided” (see the profile on Tel Afar for similar patterns).

The return of IDPs seems to follow a remarkably sectarian pattern as well. While the 915 families from Amerli’s three Turkmen Shi’a villages returned to their homes shortly after ISIL’s ouster, no Arabs or Sunni Turkmens have been allowed to return to areas controlled by the PMF, which has left the district’s entire Arab and Sunni Turkmen population uprooted. Of the roughly 70,000 Arabs (15,000 families), half have taken shelter in the Kurdish-controlled areas of Tuz Khurmatu, and the other half have fled to Kirkuk and Suleimani governorates. About 90 percent of the district’s Sunni Turkmens fled to Kirkuk.

Several informants reported an agreement made between Sunni Arab representatives from Tuz, Baghdad-based PMF leaders, and the central government in the second half of 2016, which would allow the Arab population’s return to areas controlled by the PMF. Already in October 2016, the Sunni Endowment in Samarra reported that 200 families had undergone security checks by a joint committee that was led by the head of Suleiman Bek sub-district and the military commander of Badr in Tuz.23 Yet, no one has returned to date because they fear the wrath of local Turkmen militias, which demonstrates the Baghdad-based leadership’s inability or unwillingness to enforce the deal. Asan official of Suleiman Bek sub-district eloquently put it, “the sword is mightier than the pen.”

A local Badr representative confirmed that IDPs cannot yet return to their homes, at least until Hawija is liberated, which would lessen the security pressure on the district. Besides the continued threat from ISIL (see section below), Arab IDPs also said they could not return because the Shi’a Turkmen community would then demand compensation from them for the damages caused by ISIL, which they did not have the means to pay (Arabs are viewed by many Turkmens as collectively supporting and/or not doing enough to stop ISIL). Many displaced families have exhausted their savings, and their assets are worthless, with homes destroyed and farms neglected.

The PMF also refused to permit the return of those presumed to have collaborated with ISIL or their family members – so-called “ISIL families.” The blocked return and forced displacement of “ISIL families” and suspected ISIL collaborators were common across all areas examined in the research and all liberated areas of Iraq.

Although at the time of research there were ongoing discussions about the return of the original population (of all ethnicities), the Arab, Sunni Turkmen, and Kurdish populations feared that their displacement from their original areas would be long-term and that the Shi’a PMF would ensure that the southern half of Tuz remained a Shi’a‑majority area. As evidence that Shi’a Turkmen planned to keep control, two key informants claimed that Shi’a Turkmen have started to cultivate the occupied lands of displaced Arab or Sunni Turkmen residents, suggesting they plan to stay long-term.

Patterns of PMF-property destruction also suggest an effort to permanently change the population dynamics, according to some human rights groups and local informants. Using satellite imagery and field visits, Human Rights Watch documented widespread destruction of property in 30 out of 35 analyzed Arab and Sunni Turkmen villages in PMF-controlled Tuz. Human Rights Watch reported that the property destruction was “methodical and driven by revenge and intended to alter the demographic composition of Iraq’s traditionally diverse provinces,” according to local officials and community representatives.24 Key informants interviewed for this research study tended to agree with Human Rights Watch’s findings and argued that the property destruction in PMF-controlled Tuz is similar to the patterns of sectarian appropriation in liberated areas that have been reported in other parts of Iraq (notably in Jurf al-Sahkr in Babel governorate).25 The PMF’s spokesman and deputy head of the district council rejected these allegations when asked in February 2017. He claimed that ISIL was responsible for all destruction of property but did not offer evidence to support his claims.

At the time of writing, the Arab and Sunni Turkmen residents displaced from PMF-controlled areas in Tuz were between a rock and a hard place. Although not able to return to their original areas, these communities were being forced to leave Kirkuk by local authorities, according to a 2016 human rights report by the US26 and a Human Rights Watch report from May 2017.27

Kurdish-controlled Areas

Roughly the northern half of Tuz is controlled by Kurdish forces, predominantly the PUK.28 The PUK’s Unit 70 is in charge of most Kurdish-controlled areas of Tuz and has its base in Khidr Wali town. However, Kurdish-controlled parts of the capital, Tuz Khurmatu, are mixed. In Kurdish areas of Tuz Khurmatu, there are two separate Asayish: one reporting to the PUK leadership and the other to the KDP.

The constituents living under the Kurdish Security Forces’ control, including Kurds, Arabs, and Sunni Turkmen IDPs from other parts of Tuz, generally view them positively. All of those interviewed among these groups generally praised Kurdish protection. However, many Shi’a Turkmen fear crossing into Kurdish territory, even when there are no recent reports of Peshmerga abuses of Shi’a Turkmen. Similar to the PMF, the Kurdish Security Forces in Tuz are implicated in blocking the return of displaced Arabs to areas under their control. Many Arab villages in Tuz’s central sub-district were allegedly razed during or after ISIL’s ouster, while others close to Sadiq Airbase – Hulaywa 1, Hulaywa 2, and Khashamina – were declared part of a newly designated militarized zone, rendering return impossible. Similarly, return to the three Kurdish-controlled Arab villages in Suleiman Bek sub-district has not been granted.29 Similar patterns of property destruction (to the level of entire villages) and seemingly ethnically based limits on returns have been reported in other Disputed Territories, such as Ninewa’s Zummar sub-district. These patterns have been interpreted as an attempt to change the local demographics in favor of the groups in control.

Current Security Dynamics and the Continued Kurdish-PMF Standoff

Despite the successful ouster of ISIL in 2014, there is a continued security threat in Tuz district.30 ISIL and other Sunni radical groups, such as Ansar al-Sunna, have on several occasions crossed into Tuz from the direction of Kirkuk’s Zerge village to carry out attacks against security forces and civilians in both Kurdish and PMF-controlled areas of the district.

According to the Peshmerga, ISIL engaged in direct fights and planted IEDs to target Peshmerga reinforcements and convoys transporting new shifts of fighters, which have led to many casualties among their ranks.31 ISIL attacks have also struck communities under Turkmen PMF control. During a visit to Brawchili in February 2017 (a Shi’a Turkmen village in Amerli sub-district), residents expressed concern about their continued vulnerability to ISIL attacks from right across the border in Kirkuk’s southern districts. In the subsequent months, the second commando regiment of the Northern Tigris Operations Command engaged ISIL operatives in Amerli sub-district and the adjacent areas of Kirkuk governorate, clearing about 700 square kilometers with the PMF’s 52nd Battalion.32 Meanwhile, the standoff for control between Kurdish and Shi’a Turkmen PMF forces in Tuz threatens to escalate into more serious conflict, with the mixed ethnic population of the two different areas caught in the middle. There have already been incidents of direct conflict and confrontation between PMF and Kurdish forces along the lines of control. An exchange of fire at a Tuz checkpoint on November 12, 2015, and later that day inside Tuz General Hospital sparked open conflict between the Turkmen and Kurdish communities.33 In a matter of days, the Peshmerga dispatched two regiments to Tuz Khurmatu and rolled tanks into the city’s Askeri neighborhood,34 while Turkmen PMFs established sniper posts on top of residential buildings and received significant reinforcements from Iraq’s southern cities. The conflict led to a series of abductions, killings, and widespread destruction of property on both sides. No one has been held to account to this day.35

The Kurdish-Turkmen confrontation prompted mediation at the national level on April 27, 2016, with the involvement of the Kirkuk governor, the PUK leadership, and the PMF’s top leadership, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis and Hadi al-Ameri.36 According to a key informant, Iran also played a constructive role in bringing the two sides together. As a result of these talks, a joint PMF-Kurdish force was established to patrol Tuz Khurmatu and address rights violations that could spark violence between Kurds and Shi’a Turkmens. The joint force would be drawn from the Najaf-based Imam Ali Combat Division, which had arrived in Tuz by May 1,37 and Peshmerga units from outside Tuz. Key informants suggested that the joint force has been effective in preventing the escalation of the conflict between Kurds and Turkmens. However, some raised concerns that a large number – between 50 – 70 percent – of the Imam Ali Combat Division fighters had been diverted away from Tuz to participate in the Ninewa operations before February 2017, undermining the joint nature of the force and decreasing its overall manpower.38

In terms of implementation of other commitments from the April 2016 talks, Turkmen PMFs immediately disassembled their sniper posts, and the Peshmerga immediately removed its tanks from PMF-controlled Askeri neighborhood. The Peshmerga handed over control of the district’s southern, external checkpoint to GOI Security Forces in 2017. However, there has been less progress on other commitments in the agreement. For example, local PMF representatives have not participated in any session of the district’s new joint security committee, which would in theory include all relevant security actors to advise the mayor. Other steps aimed at demilitarization, such as the removal of concrete barriers in Tuz Khurmatu city’s Shi’a Turkmen neighborhoods, were not implemented.

There has also been little progress in addressing other Turkmen grievances. Shi’a Turkmens feel they are not represented proportionally in local government. Most heads of directorate are led by Kurds, including health, municipality, and engineering (but the local police is led by a Shi’a Turkmen). Moreover, Turkmens watch with suspicion the ongoing construction of watchtowers in two KRG-SF military bases that are wedged in Tuz Khurmatu city’s Turkmen-controlled neighborhoods, and many demand that Peshmerga remove all forces from the city’s so-called Turkmen areas (i.e., south of the Tuz-Tikrit road).

With tensions not ebbing, a Kurdish delegation visited Sistani’s office to ask for mediation between Kurds and Turkmens in December 2016, one year after fights erupted between the two communities. On February 11, 2017, a delegation from Sistani’s office met with two reconciliation committees representing each side in Tuz.39 A few months later, the parties met again, but there has been no tangible outcome of these efforts so far. Many anticipate further escalation, driven by a strong conviction that the “other” side will not be able to put up a united front.40 Abu Ali, the local commander of League of the Righteous proclaimed, “The next will be the last straw with the Kurds!”

Conclusion

With the recent anti-ISIL operations in Ninewa and other parts of Iraq, there is comparably less attention paid to areas like Tuz that have already been cleared. However, Tuz merits more attention because it provides a cautionary tale to Iraqi and foreign decision-makers about the difficulty of stabilization in areas of disputed control, where former allies in the fight against ISIL might quickly turn against one another.

Although recent mediation efforts have helped de-escalate the conflict between the Kurdish Security Forces and the PMF, the overall take-away from the current situation in Tuz offers little room for optimism. With so many grievances unaddressed, “the fire is smoldering under the ashes,” as Mohammed Mehdi al-Bayati, the Badr representative and Minister of Human Rights from 2014 to 2015, put it. Moreover, despite national-level agreements permitting return, there has been no progress in the plight of Sunni Arabs and Sunni Turkmens because these displaced communities fear the vengeance of local Turkmen PMFs.

The looming ouster of ISIL from its remaining areas of open control will likely increase Baghdad’s current, low levels of attention to the security and political dynamics in Tuz (similar to other strategically important districts examined in this research). But here, perhaps more than anywhere else, any effort at reconciliation of sectarian and ethnic grievances will also be predicated on the leadership of Iran and Turkey, given their sway with different communities in Tuz.

References

1 This paper builds primarily on 40 key informant interviews conducted in February-March 2017 by the author and two local researchers, Ammar Ahmmed and Mohamed Faiq, in Tuz Khurmatu city, Brawchili town, and Khidr Wali town with political representatives (9), local security actors (8), civil society representatives (7), and people displaced from areas to which the team had no access (16), including Amerli, Hulaywa, Suleiman Bek, and Yengice.

2 Andrew Whitley, Genocide in Iraq: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1993), https://www.hrw.org/reports/1993/iraqanfal.

3 Human Rights Watch, Endless Torment: The 1991 Uprising in Iraq and Its Aftermath (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1992), www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/1992/Iraq926.htm. The same year, Nawjul sub-district was separated from Tuz and placed under the administration of Diyala governorate’s Kifri district, which is viewed by locals as a measure to further divide Kurds and Turkmens.

4 Sean Kane, Iraq’s Dispute Territories: A View of the Political Horizon and Implications for U.S. Policy (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 2011), https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/resources/PW69.pdf.

5 For all of these estimates on demographics, there are no detailed statistics available. Key informant interviews suggested highly variable estimates. Informants also noted that there are no Shi’a Arabs or Shi’a Kurds living in the district.

6 Based on the Salah ad-Din Provincial Council’s decision in January 2016, Amerli sub-district became a district of its own effective January 2017, spurring debates over whether the new district would be considered in the eventual referendum under Constitution Art. 140. For practical reasons, we consider Amerli as part of Tuz district in this paper.

7 For example, there was an exchange of fire after the Northern Tigris Joint Operations Command (which Prime Minister al-Maliki set up to secure the Disputed Territories) attempted to strip the Tuz PUK party headquarters of its weapons on 17 November, 2012, leading to a heated conflict between the KRG and Baghdad. The head of Northern Tigris Operations Command accused 600 Kurdish officers and soldiers of its 16th Brigade, stationed in Tuz a year later, of disobeying orders and siding with the Kurdish Regional Government during this conflict. MA, “Abd al-Amir al-Zaidi Refers 600 Kurdish Officers and Soldiers to Trial for Disobeying Orders,” Almada Press, June 12, 2013, https://www.almadapress.com/ar/NewsDetails.aspx?NewsID=13463.

8 Michael Knights, Saving Iraqi Turkmens is a Win-Win-Win (Washington, DC: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2014), http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/saving-iraqi-turkmens-is-a-win-win-win.

9 For example, on 25 June, 2013, two suicide bombers attacked a sit-in organized by Turkmens to protest the lack of security in the district, leaving 22 people dead, including a leader of the Turkmen Front and a senior government official. “Iraq 2013: A Year of Change,” Russia Today, 2013, https://iraq2013.rt.com/en.html.

10 The siege of Amerli town was taken so seriously that Hezbollah Brigades even helicoptered in 50 of their best fighters. Babak Dehghanpisheh, “Special Report: The Fighters of Iraq Who Answer to Iran,” Reuters, November 12, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-militias-specialreport-idUSKCN0IW0ZA20141112.

11 The involvement of the United States Air Force was rejected by all consulted informants in Tuz, despite the claims made by Foreign Policy and Human Rights Watch. Susannah George, “Breaking Badr,” Foreign Policy, November 6, 2014, foreignpolicy.com/2014/11/06/breaking-badr/; Human Rights Watch, After Liberation Came Destruction: Iraqi Militias and the Aftermath of Amerli (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2015), https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/03/18/after-liberation-came-destruction/iraqi-militias-and-aftermath-amerli.

12 President of the Sunni Waqf in Sammarra, Report on Suleiman Bek and Amerli, October 1, 2016.

13 Despite the district’s needs, local government representatives claimed that it has not received any financial support from the KRG or the central government since 2014 and that infrastructure projects approved before 2014 – such as the expansion of the Tuz General Hospital to accommodate 1,000 people and sewage works – were indefinitely stalled. The UNDP’s Funding Facility for Stabilization has also not approved reconstruction projects in the district. United Nations Development Programme in Iraq, Funding Facility for Immediate Stabilization Progress Report Quarter III- 2016 (New York: United Nations Development Programme in Iraq, 2016), http://www.iq.undp.org/content/iraq/en/home/library/Stabilization/funding-facility-for-immediate-stabilization-progress-report-qua0.html.

14 Announcements of the Tigris Operations Command, Second Commando Regiment, “Update.” Facebook post. June 2, 2017. https://goo.gl/PdUQeX.

15 The role of the Khorasani Brigades in today’s Tuz is unclear. Key informants suggested they stayed as a launching pad for an eventual confrontation with Kurds in the Kirkuk area. The Khorasani Brigade was not available for comment.

16 As one PMF leader explained, “You will join the militia that liberated your neighborhood.”

17 Rashid Kareem Ahmed set up a new unit of 100 fighters in early 2017 in Tuz Khurmatu city (Brigade 16). 600 Sunni fighters in Brigade 52 have been active in Kirkuk’s Hawija area since 2015. For more information, see the discussion of Brigade 52 in the Kirkuk briefing profile.

18 The League of the Righteous stands apart from the rest because its leader defines the group as a combat force [quwa dhariba], which does not hold territory. This group also differs in that only half of its fighters are locals, and the rest are from southern governorates and undertake special missions [muhammat khassa]; most of its local fighters have not been recruited recently because the group has been clandestinely active in the area since 2003. It is also the only consulted group that openly admitted to interrogating suspects (e.g., after a local policeman was killed in early 2017, the League of the Righteous arrested and interrogated three suspects and then handed them over to the local police, according to its commander). Outside of Tuz Khurmatu city, the League of the Righteous has a military base in Badr-controlled Suleiman Bek.

19 Emergency Room Statistics in 2016. Tuz General Hospital.

20 Human Rights Watch, Iraq: Ethnic Fighting Endangers Civilians: Kurds, Turkmen, Arabs Clash in Northern District (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2016), https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/13/iraq-ethnic-fighting-endangers-civilians.

21 “Dead and Wounded from the Security Forces, Including the Police Chief of Tuz, following an Attack by Daesh on Amerli,” Shafaaq, June 17, 2016, http://www.shafaaq.com/ar/Ar_NewsReader/9dde9ebb-6df8-4063-a8fd-e2732cb29f81.

22 “News of the Militias Continuing to Carry out Mass Executions in the Ameri Prison in Diyala,” Al-Quds al-Arabi, June 23, 2016, www.alquds.co.uk; Omar Awar, “Secretary General of the Council of Arab Tribes: 52 – The Number of Prisoners Executed by the Hashd Militia in the Prison of Ameri,” Bas News, June 19, 2016, www.basnews.com/index.php/ar/news/iraq/282494. Interviewed PMF commanders expressed concern over the judiciary system, claiming that ISIL detainees would often get out of prison in Tikrit and other Sunni Arab-majority locations in Salah ad-Din with the use of wastas [influential intermediaries] or simply paying off judges or prison wardens and guards. They did not confirm operating separate detention facilities, despite some allegations.

23 President of the Sunni Waqf in Sammarra, Report on Suleiman Bek and Amerli.

24 Human Rights Watch, After Liberation Came Destruction.

25 “Allawi: The Return of IDPs to Jurf al-Sakhr is in Iran’s hands,” al-Jazeera Arabic, May 4, 2017.

26 United States Department of State, Iraq 2016 Human Rights Report (Washington, DC: United States Department of State, 2017), https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2016/nea/265498.htm.

27 Human Rights Watch, Iraq: Kirkuk Security Forces Expel Displaced Turkmen, Threats, Abuse against Sunni Families in Kirkuk (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2017), https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/05/07/iraq-kirkuk-security-forces-expel-displaced-turkmen.

28 Of the seven Kurdish seats in the district council, the PUK currently has four seats, the KDP two, and the Communist Party one.

29 The three villages are Kukis, Khasa Darli, and Yafa. President of the Sunni Waqf in Sammarra, Report on Suleiman Bek and Amerli.

30 “Brigade 52 (Badr) Arrests 3 Men Who Were Planning to Target Al-Azim Dam,” Al Ghadeer TV News, February 16, 2017, http://www.alghadeer.tv/news/detail/50565/.

31 “ISIL is Launching an Offensive on the Tuz Front,” Rudaw, April 3, 2015, http://www.rudaw.net/arabic/kurdistan/0403201511.

32 “Brigade 52 — Badr: More than 700 Square Kilometers Cleared in the Vicinity of Amerli and Northern Diyala,” Badr News, May 17, 2017, badrnews.net/home/single_news/61398.

33 Human Rights Watch, Iraq: Ethnic Fighting Endangers Civilians.

34 “Peshmerga Strengthens its Presence in Tuz Khurmatu with Two Battalions from Kurdistan,” Alghad Press, November 8, 2016.

35 Human Rights Watch, Iraq: Ethnic Fighting Endangers Civilians.

36 “The Start of a Meeting to Calm the Situation in Iraq’s Tuz District,” Al Quds Al Arabi, April 27, 2016, http://www.alquds.co.uk/?p=523223.

37 Tuz Khurmatu, “Arrival of the fighters of Imam Ali Combat Division to Tuz,” Facebook post. May 1, 2016. https://www.facebook.com/tuzkhurmatueli/posts/463047677228215.

38 According to a recent report, all 400 fighters of the Imam Ali Combat Division left Tuz on June 28, 2017. “Withdrawal of PMF from Tuz,” Al-Gharbiya News, June 28, 2017, https://www.algharbiyanews.com/?p=82210.

39 The Kurdish committee includes a PUK representative, the mayor, a member of the district council, a representative of the Sunni Endowment [waqf], and four other civil society representatives (religious and tribal leaders and lawyers). “Participants in the Mediation Committee,” Memo (soft copy), February 11, 2017, Tuz Khurmatu. The Turkmen committee includes the leaders of 10 PMF factions and five civil society representatives.

40 “The Turkmens are divided; some follow Turkey, and others follow Iran.” (Kareem Shukour Muhammad, PUK leader of the 16 Hamreen electoral district); “The Kurds do not pose a real threat to Turkmens as long as they are divided.” (Mohammed Mehdi al-Bayati, political representative of the Badr Organization).