Iraq after ISIL: Qaraqosh, Hamdaniya District

Local Christian and Shabak forces vie to police this decimated ghost town and surrounding Christian areas, a part of the larger Baghdad versus Kurdish competition and demographic reshaping of the Ninewa Plains.

This research summary is part of a larger study on local, hybrid and sub-state security forces in Iraq (LHSFs). Please see the main page for more findings, and research summaries about other field research sites.

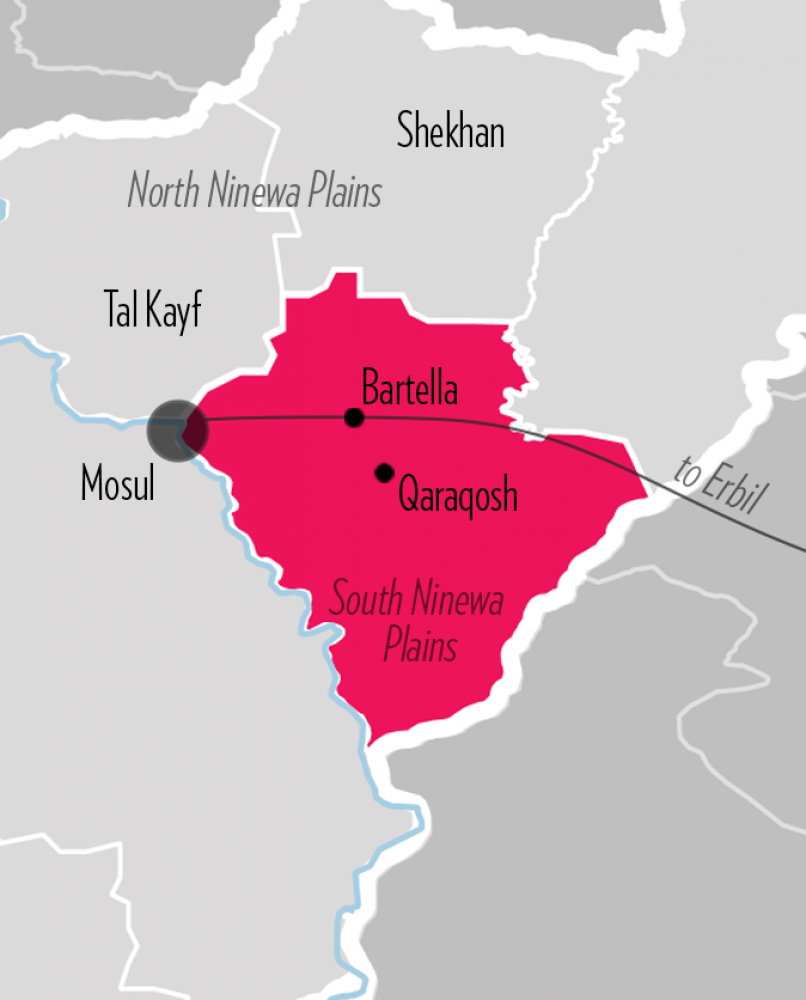

Hamdaniya district, approximately 32 km southeast of Mosul and 60 km west of Erbil, together with Tel Kef and Shekhan districts constitute an area known as the Ninewa Plains, which is home to many of Ninewa’s minority communities and a central part of the Disputed Territories. The ISIL invasion in the summer of 2014 was especially brutal for the Yazidi, Shabak, and Christian minorities of the Ninewa Plains.2 Hamdaniya was nearly emptied of its historical-majority Christian populations. An estimated 125,000 people fled from Hamdaniya, and most of those left behind were brutally executed or enslaved.3 ISIL’s treatment of minority groups in the Ninewa Plains has since been deemed an act of genocide.4

After facing such an existential threat, many within these minority communities responded by taking up arms. Multiple micro-LHSFs sprung up among different minority factions across the Ninewa Plains in the name of community self-defense. However, these groups are too small and too politically marginalized to stand alone in the hyper-competitive security and political environment. Each has allied with larger security actors, including Kurdish forces, the Iraqi Government in Baghdad, and southern Shi’a PMF, which puts them in the middle of the ongoing Baghdad-KRG competition in the Disputed Territories.

The small town of Hamdaniya is the district capital, but Qaraqosh, Iraq’s largest Christian city, has long been the larger population center and hub in the district. Qaraqosh illustrates an extreme end of the spectrum in terms of displacement, return, and reconstruction. The formerly thriving town of 50,000 is a ghost town with almost no return or reconstruction. The situation and political dynamics in Qaraqosh, and to a lesser extent those in nearby Bartella, will be the focus of this research study. However, many of the trends happening in these towns and in Hamdaniya district also exist in other parts of the Ninewa Plains.

Key Facts: Qaraqosh

Population: 226,367 (district); 50,000 (Qaraqosh town)

Ethnic Composition: Majority Assyrians, Chaldeans, Syriacs (all Christian communities of diverse denominations); significant number of ethnic Shabak (majority Shi’a, minority Sunni), Kurdish and Arab minorities

Date taken by ISIL: August 6-7, 2014 (Qaraqosh)

Date reclaimed: end of October 2016

Ground Forces engaged in clearing: Primarily Iraqi Army

Overall Control: ISF

LHSFs present: NPU (local PMF) in Qaraqosh; Babylon Brigade (local PMF) in Bartella; other local Christian groups (NPF, NGPF) nearby

Key Issues:

- Return of population and reconstruction not beginning

- Competition between KRG and Baghdad, realized via competing local groups

Background and Pre-ISIL Dynamics

The pre-2014 population of Hamdaniya was estimated to be 226,367:5 a mix of Christians of diverse sects and denominations, including ethnic Chaldeans, Assyrians, and Syriacs;6 a significant Shabak community;7 and a very small, minority Arab population. Historically, Hamdaniya’s landscape has been dominated by a cluster of mid-sized Christian towns – Qaraqosh (estimated 50,000 persons), Bartella, and Qarambles – surrounded by smaller Shabak villages. However, the demographics have been shifting in the few decades. Under the Saddam regime’s Arabization policy in the 1980s, Arab tribes and officers were granted tracts of land in Hamdaniya. Shabaks in the area were also encouraged to register as Arabs (not Kurds) in exchange for plots of land.8

Some of these demographic shifts continued beyond the Saddam era. Locals reported a surge of Shabak community members purchasing land and homes in predominantly Christian cities prior to the 2005 and 2009 elections, particularly in Bartella, which caused friction between the Christian and Shabak communities. Some Christian Qaraqosh residents interviewed said the homes and land purchased were often relatively expensive. Given the relatively low economic means of most of the Shabak community, these residents suspected that Shabaks had been given money by Baghdad-based Shi’a groups (the majority of the Shabak identify as Shi’a, although there is variance). These recent historical frictions and the perception, at least, on the part of some Christians that Shabak or other minority groups’ territorial expansion threatens their political interests are important background to the current tensions between Shabak and Christian militias in the Ninewa Plains.

While these trends resulted in increased Arab and Shabak populations, the Christian population also grew because Christian minority communities from other parts of Iraq came under great threat in the post-Saddam era and moved to Qaraqosh for safety. Though population numbers are always difficult to estimate given the lack of regular census in Iraq, one UN estimate suggests the population may have increased by 30 percent from 2008 to 2016, having already increased 50 percent in the decade prior to 2008.

Hamdaniya is one of the six districts in Ninewa that the KRG government laid claim to as part of the Disputed Territories (in addition to Sinjar, Tal Afar, Tilkaef, Sheikhan, and Makhmour).9 It was among the weaker of the KRG’s claims. A 2008 United States Institute for Peace report by Sean Kane forecast how parts of the Disputed Territories might vote in an Article 140 referendum based on the level of local electoral support for pro-KRG parties in the 2005 to 2010 elections, the administrative history of these areas, and recent demographic changes.10 While pro-KRG parties generally attracted more than 70 percent of the vote in Makhmour, Sheikhan, and some subdistricts of Talkayf and 50 percent in neighboring Bashiqa subdistrict, in Hamdaniya, pro-KRG parties never gained more than 35 percent of the vote. In addition, prior to 2014, security and administrative control in Hamdaniya was always provided by Iraqi security forces. While the level of security provided by Baghdad was insufficient to address the security threats that emanated from nearby Mosul and that were often directed at minority communities, KRG forces did not extend patrols into Hamdaniya as they did into neighboring areas in Talkaef. However, in 2004 KRG leaders did begin to fund a local neighborhood watch group, the Ninewa Guards Protection Force, a pre-cursor to one of the local Christian forces that exists today.11

ISIL Capture, Expulsion of Population, and Abuses

When Mosul fell to ISIL and the Iraqi Army abandoned their positions around the city and neighboring districts, Peshmerga forces moved in and began to form a defensive line across the Ninewa Plains, including Hamdaniya, promising to defend the area.12 However, according to BBC reporting, late on Wednesday August 6, 2014, Peshmerga told Qaraqosh’s Archbishop that they would not be able to defend the town and fled from their posts; the town was taken overnight.13 Former residents described their midnight flight from the city. One former resident and Christian political leader, Khalid Ayshoa Estaiffo, remembered,

“We had half an hour’s notice. I was there and left Qaraqosh only in the last hour. There were Peshmerga there. They were in front of Qaraqosh, defending [the town], and we asked them for a situation update. They said, ‘we will not retreat even if all of us are killed.’ So we had this guarantee.” For this reason, he said, the community had not prepared to evacuate, but then the bombs started falling. “Two kids and one lady – 30 years old – were killed instantly, and many were injured. This was like a message to us to get out.”

Estaiffo said that most of the 50,000 residents fled, but he estimated that about 400 people chose to stay behind. Some were captured by ISIL, and others were brutally killed, their deaths broadcast on social media. Eye-witness reports confirm that those who were not able to escape were subject to torture, public executions, and crucifixions.14 In addition to these acts of torture, Christian families from Qaraqosh had daughters who were kidnapped and sold into sexual slavery, where they faced routine sexual violence by ISIL fighters and were often passed among men as “gifts.”15 Reports have not yet confirmed how many of ISIL’s sexual slaves are specifically Christian women, though some estimates indicate this number could be as high as 1,500.16 Estaiffo said that within the Qaraqosh community, at least 75 women and girls were known to be captured by ISIL.

ISIL completely looted and destroyed Qaraqosh. It was one of the more extreme examples of the group’s deliberate destruction of the communities they captured, surpassed only by their treatment of the Yezidi community in Sinjar. In a visit to the town in February 2017, no home, building, church, or other property appeared untouched. It was an entire town of jagged windows and burned-out husks of buildings. Most appeared to have been torched from inside by explosives. According to data by the Ninewa Reconstruction Committee, 13,000 homes in the Ninewa Plains need to be rebuilt – around 7,000 in Qaraqosh alone.17 Churches and other religious facilities were systematically looted, with religious symbols broken or destroyed. A visit to one church revealed a sort of factory for making suicide bombs and explosive in the annex that had previously been used as a church choir room.

Similarly high levels of destruction were apparent in the nearby town of Qarambles and in parts of Bartella. Although structures were still standing, nearly all the windows were blown out, and the walls were pocked with shrapnel and bullet holes. In parts of Bartella, it appeared that at least one home per block had completely collapsed due to damage.

Displacement was total, and while significant numbers of the Christian community fled to the nearby KRG or, to a lesser extent, other parts of Iraq, many left Iraq entirely.18

Recapture and Emergence of Local Defense Forces

Operations to recapture Hamdaniya district and surrounding areas took place between October 17 and 22, 2016, through joint Kurdish and Iraqi government operations. A mutual KRG-Baghdad agreement divided responsibility for taking different parts of the Ninewa Plains area, and the ISF led the campaign in the southern Ninewa Plains. Both Bartella and Qaraqosh were re-captured around October 22.19 The Peshmerga retook Bashiqa a few weeks later, between November 7 and 11, 2016.20

Given the scale of destruction in Qaraqosh and the deep mistrust at having been abandoned (first by Iraqi forces, then by the Peshmerga), there has been virtually no return to the town. According to data from the Ninewa Plains Reconstruction Committee, by July 2017, 403 families had returned to Qaraqosh – less than 5% of the population pre-ISIL.21 Many of those still maintain a secondary residence in Erbil or other nearby areas and have only returned to begin restoring their houses. While reconstruction support has been approved, implementation has been slow, and there are no basic services in the city. The electricity supply in Qaraqosh largely depended on a power station in Mosul that had not yet been prepared at the time of research.

As a result, during the period of research in February 2017, Qaraqosh and Qarambless were ghost towns. In Qaraqosh, there were only the local defense forces stationed at checkpoints (to be discussed shortly) and a handful of residents, who appeared to be mostly there to sell refreshments to the forces stationed in the town.22 By contrast, although Bartella was also severely destroyed and some of its worst-affected neighborhoods still appeared deserted, there were signs of growing return and of normal life. In the part of the town near the road toward Mosul, traffic was booming, and the markets were lively.

The contrast between the towns has increased as time has gone on. By the time of writing, some of the commercial and cultural life previously centered in Mosul had re-opened in Bartella (for example, a satellite campus of Mosul University), kickstarting the local economy and increasing the return of normal civilian life. Many of the returnees are not the original residents, however. Bartella was previously a predominantly Christian town, but the majority of its Christians have not returned, similar to the lack of return in Qaraqosh and other Christian areas. Those who have returned are Bartella’s original Shabak population, Shabak who previously lived in surrounding areas, and a new flood of Arab IDPs. The new demographics in Bartella and the contrast between this town’s levels of return and reconstruction and those of other key Christian towns are illustrative of significant changes in the political and security dynamics of the Ninewa Plains, which are a result of post-2014 shifts. Many of these changes have to do with the politics surrounding local armed groups.

Since ISIL’s rise and the abandonment and devastation of minority communities, local security and defense forces have proliferated in the Ninewa Plains. Each of the minority groups across the Ninewa Plains – including multiple Yezidi forces, Shabak forces, and, most pertinent to this paper, a range of Christian forces23 – has mobilized local self-defense forces from among its communities. Although there are likely numerous minor splinter forces and some fluidity in terms of new groups forming, four different Christian forces come up most commonly in discussions of security dynamics in Hamdaniya and the surrounding Ninewa Plains areas:

- Ninewa Plains Protection Unit (NPU) – NPU are an Assyrian Democratic Union-sponsored force that officially come under the PMF umbrella, but, unlike the Babylon Brigade (discussed below), they have some degree of independence and a different agenda from the larger Shi’a PMF units. They are the only Christian militia to receive official, US-led Tribal Mobilization Force (TMF) training and are currently holding the southern Ninewa Plains around Qaraqosh.

- Ninewa Plains Guard Forces (NPGF) – The largest and most long-standing force, the NPGF boasts approximately 2,500 fighters and has been around in some form since 2004. They were initially formed as a neighborhood watch force to protect churches and religious sites and have been supported by KDP officials since that time. Following the ISIL attack and crisis, the NPGF forces increased and received basic training organized by the Ministry of Peshmerga. They are now officially part of the KDP Zerevani, according to NPGF leaders interviewed.

- Ninewa Plain Forces (NPF) – Shortly after ISIL took over Hamdaniya in August 2014, the Bet-Nahrain Democratic Party and the Bet-Nahrain Democratic Union reached an agreement with the Ministry of Peshmerga to form a Christian unit under the Peshmerga.24 They tend to act as an auxiliary or supporting unit fighting alongside KDP Peshmerga, including in some frontline activities. Together with the NPGF, they have been assigned to help hold northern Ninewa Plains areas near Tal as Soqf.25

- Dwekh Nawsha (literal meaning, “the one who sacrifices”)26 – The Dwekh Nawsha are connected to the Assyrian Patriotic Party and at the time of research were mostly operating near Tel as Soqf, north of Mosul. The number of fighters is estimated to range from 50 to 100 men (with one outside estimate suggesting as many as 250 potential volunteers) and includes a handful of international volunteers.27 They reportedly receive some weapons and funding from the KDP, but they are not official sub-units of Kurdish forces, as the NPGF or NPF are.

Many of the Christian forces also rely on donations from abroad, both private charities and some foreign states (notably including explicit allocations from the US Congress to Christian militias.28

A final important group within the Hamdaniyya and Ninewa Plains context are the Shabak forces. As noted earlier, although the majority of the PMF groups are drawn from Shi’a forces raised in the south, the PMF also includes a group of Shabak Shi’a fighters, who draw a substantial number of their fighters from the Ninewa Plains area. The Shabak PMF are organized under the 30th brigade and though they have their own political sponsor and direct commander,29 they are under the leadership and direction of Badr in practice. With its Shabak leadership, this roughly 1000-man unit is comprised mostly of Shi’a Shabak and Shi’a Arab fighters. Additionally, the 30th Brigade includes a now notorious sub-force known as the Babylon Brigade, which is led by a Christian commander Rayan al-Kildani. Despite that al-Kildani is himself Christian, the majority of fighters in his sub unit are also Shia Arab. The total number of fighters is roughly 1000 men forces, and is predominantly made up of Shi’a Shabak and Shia Arab fighters. These Shabak forces has been actively involved in both frontline fighting and in holding areas, and have gained a reputation for harsh treatment and retaliation against Sunni Arabs.30 This unit continues to control many of the checkpoints in Bartela and on the outskirts of Mosul, but the brigade’s units have also accompanied PMF in operations in other parts of the Ninewa province (including in Qayarra and Nimrud).

A strong narrative of local communities taking up arms to defend themselves runs across all of these groups. The NPGF-affiliated representative Khalid Ayshoa Estaiffo described the need to mobilize Christian forces as part of a way to restore faith in the larger Christian community, who doubted that they could ever be secure in the Ninewa Plains again after having been attacked and abandoned by their non-Christian neighbors. “We are trying now to bring back their [the Christian community’s] confidence…First, [through] some kind of protection, with our Christian soldiers,” he said. A politician affiliated with the NPF, Yousef Yakoub, explained the decision to mobilize Christian forces as both a response to the local population’s demands for protection and an important gesture for future political survival: “At a political level, if we want to argue for something [and some rights], we have to have a basis…You don’t want them [larger Kurdish or Iraqi forces] to hold over us that they have given martyrs [sacrificed soldiers] in this operation [to liberate Christian areas].” For this reason, he said Christian forces had to be seen taking part in their own community’s liberation and spilling their own blood for the cause in order to have a degree of legitimacy and credibility in demanding political control in the future. However, he said that mobilization was also a response to popular demands for self-defense. “Originally this idea came from the political side, but ultimately it was also an answer in response to the people – that we need to liberate our cities and villages and soon. […] For this reason, we made this force.”

Contests for “Local” Control

Although these militias may have been mobilized on a theory of self-defense, there is pragmatic acceptance that they cannot actually stand alone.31 Cognizant that they are bit players sandwiched between much larger political interests and forces, each of these groups looks to larger forces in the area for support and backing. However, divided views over who might best protect the Christian community in the future have created a split between the different Christian groups, resulting in both Baghdad and KRG having their own affiliated local Christian forces. The Ninewa Plains Guard Forces (NPGF), the Ninewa Plain Forces (NPF), and Dwekh Nawsha are supported by different Kurdish forces. The Ninewa Plains Force (NPU) and the Babylon Brigades are part of the PMF umbrella and are supported by the Iraqi Central Government (but with the Babylon Brigades much closer to the Shi’a PMF than the ISF).

Both Baghdad and the KRG see a value in having local forces control local areas, especially in these sensitive minority areas, but they want their local forces to be the ones doing the controlling. With the ability to control an area comes the ability to control who returns to it, which can increase key actors’ ability to shift demographics in anticipation of a future Article 140 referendum on the status of the Displaced Territories. Control of the area through local actors also offers other advantages: although Shi’a PMF were deliberately not assigned to “hold” areas around Mosul (given the sensitivities of having a Shi’a force control parts of such a symbolic Sunni area), they can effectively control the area through the Shabak militias. Having their Shabak affiliates based in a place like Bartella offers Shi’a PMF fighters an informal base for other activities in the area, enabling them to influence local political and security dynamics. During the field research, PMF political headquarters had been informally established across Bartella, and there were frequent reports of Shi’a PMF manning checkpoints with their Shabak affiliates in Bartella and surrounding areas and engaging in other sporadic (and unauthorized) activities in parts of the Ninewa Plains.

While each of the Christian and Shabak local forces may have their own idea of which communities they would like to defend, based on their political agenda or the origin of most of their fighters, where they are deployed depends instead on the side they are affiliated with and the KRG-Baghdad agreement on who controls which area. For the most part, similar to other contested areas, control of an area follows the Pottery Barn rule of “You break it, you buy it”: the forces that captured an area from ISIL initially took responsibility for holding that area afterwards. Peshmerga forces led many of the operations to retake Christian communities north of Mosul and around Tal Kayf and Tal as-Soqf, and, for that reason, the Kurdish-affiliated NPGF, NPF, and Dwekh Nawsha are active in those areas. Under the Baghdad-KRG agreement at the time, ISF took the lead in re-capturing the southern Ninewa Plains, and so Baghdad-affiliated local forces are currently assigned to hold those areas. Shabak militias control checkpoints from Bartella up to the outskirts of Mosul, while the PMU (the one Christian group in the PMF) control Qaraqosh.

Control may be a strong word for NPU activities in Qaraqosh. There has been virtually no permanent return in Qaraqosh and so no real life to regulate or control. Residents have occasionally come back to check on their property, but they continue to live in the parts of the KRG or other areas where they have been residing since being expelled in mid-2014. On visiting the town in February 2017, the small clutch of NPU forces at the checkpoints leading into Qaraqosh and in the town’s NPU headquarters appeared to be the only souls around, save for a few vendors supplying water and snacks to the soldiers. Although the signs of ISIL are everywhere in the shattered face of the town, the absence of people also means an absence of sleeper cells or other prevailing ISIL threats.

The degree to which the NPU actually control Qaraqosh is also undermined by other security actors in the surrounding areas. The NPU in Qaraqosh are hemmed in on all sides by stronger forces who do not necessarily support them or Christian autonomy in general. Entry into Qaraqosh from Erbil is tightly controlled by a series of Kurdish checkpoints. During the research period, although NPU leaders were willing to arrange a site visit to Qaraqosh, they were unable to obtain permission from the KRG for researchers to do so. Their effective control and authority only reaches to the perimeter of a deserted shell of a town. This situation applies not just to journalists or researchers, but also to residents. Although Qaraqosh residents are in general allowed to return and many have been back to check on their property, if not to stay, permission to do so might be withheld at times depending on security and political dynamics. For example, permission to visit Qaraqosh was denied to residents and others for several weeks when the West Mosul operations kicked off. These limitations are not due to KRG-NPU tensions specifically. The same issues prevented researchers in this study from visiting the northern Ninewa Plains areas around Tal As-Soqf, which are held by KRG-affiliated Christian groups. Although the NPF and NPGF were willing to arrange a site visit or tour with forces in this area, their authority did not extend to being able to negotiate access through the myriad Kurdish checkpoints en route to the areas they “controlled.” What this illustrates is the overall weakness of Christian forces vis-à-vis the surrounding forces, and their lack of autonomy even when they are nominally given control of a local area.

The NPU’s authority in Qaraqosh is further constrained by the close proximity of Shabak forces in nearby Bartella. The Shabak militias are a more numerous and aggressive force, and they are backed by powerful Shi’a PMF forces. Shabak militias have recently gained a reputation for perpetrating abuses in the Ninewa Plains areas, and, where they do so, Christian militias are not strong enough to stop them. Although more of these abuses have targeted Sunni communities in retaliation for ISIL abuses, there have been allegations of Shabak looting and damage in Christian areas like Qaraqosh in the immediate wake of ISIL’s ouster (presumably to deter Christian return).32 The threatening presence of Shabak militias in close proximity is one of the factors deterring the return of the Christian community to Qaraqosh and nearby Christian areas (although the level of damage, former residents’ doubts of ever being safe in that area, and comfortable resettlement in other areas are also factors).33 All Christian leaders interviewed said that their authority and position were threatened by the Shabak militias. Given the history of increasing Shabak ownership and population growth in Christian cities in the decade prior to ISIL’s rise, Christian communities fear that the Shabak communities will use this moment of flux to seize a greater claim over cities like Qaraqosh, starting with the Shabak militias’ seizure of security responsibilities.34

An additional source of tension, if not open conflict, is the competition between Christian groups. Each of the four Christian defense forces aligns with one or more of the seven main Christian political parties, and their members draw from across the Ninewa Plains. A substantial percentage of the forces in all of these four groups come from Qaraqosh city or surrounding areas in the southern Ninewa Plains. However, as noted earlier, deployment locations for Christian forces depend on whether they are affiliated with the KRG or Baghdad, not where they come from. A Christian fighter from Qaraqosh who is motivated to liberate his city might have joined the NPF because it matched his political affiliation, but because the NPF is KRG-affiliated, he would find himself liberating other Christian areas and kept from operating in his own hometown. The NPGF, which originated out of Qaraqosh in 2004 and identifies strongly with protecting the town, is also KRG-affiliated and so not permitted to take part in defending the southern Ninewa Plains. This manner of dividing the different Christian forces’ areas of operation creates internal tension and competition between the different groups, with both the NPU and NPGF arguing that they are better suited to hold Qaraqosh.35

Some of the Christian political leaders interviewed said there have been discussions about how to bring the different Christian factions and defense forces together to present a unified front and a stronger, collective counterweight to other ethnic armed groups in the area. For example, a politician affiliated with NPF forces, Yousef Yakoub, argued that the best route would be to “create a self-defense, including all the volunteers from all our forces, in one professional force…not to have these different militias affiliated with different parties. Two and a half years ago, it was necessary, but now that moment is over.”

Other Christian leaders seem less focused on unity and instead are placing their bets on one side or another of the Baghdad-KRG competition, depending on which side seems to offer the best prospects for protecting minority communities in the future. KRG-leaning Christian leaders tend to point to the continued security threats leading up to ISIL control and the ISIL takeover to argue that they cannot trust their Arab neighbors and the Baghdad-based government to protect them. Meanwhile, those leaning more toward Baghdad tend to point to the Kurdish forces’ abandonment of the city.

Still others suggest that the ideal solution would be political autonomy from all sides. In an interview, NPGF-affiliated representative Khalid Ayshoa Estaiffo explained the lack of confidence that many Christians have in either side: “More than 30 – 35 percent [of the Christian community] have emigrated out of Iraq. They have lost confidence in the future of living here and confidence and trust in the communities around us. These are the communities who burned our houses and stole everything. We see how Muslims think…we will never convince them that we are equal. […] This extreme Islamic attitude will rise again wherever there is an environment that enables it.” As a result, he said, the best solution in his opinion was for the Christian community and each of the minority communities (including the Shabak, Yezidis, and Kakais) to have their own self-rule. For example, this solution would give the minority communities their own governorate resulting from an Article 140 referendum process and guaranteed by the international community. “Justice is to have our own autonomy, to govern our own area and make our own rules, to enjoy our own religion, culture, psychology,” he said.36

The prospects for Christian autonomy seemed slim at the time. These local actors have minor strategic importance at the moment; they can help control local territory and in the near future may enhance each side’s claim in the Disputed Territories. However, these abilities will not necessarily give them enough leverage to secure their long-term goals. As Yousef Yakoub suggested, “The risk is that whichever one wins out [Baghdad or the KRG], we are a small number of fighters, and we can be pushed aside.” Ultimately, though, he thought the worst-case and most likely scenario would be that the current stalemate, with both sides competing with each other and local actors held in limbo. “If there will be a decision on these, then I’m optimistic, but if they just let it go as it is, then it will get worse.”

References

1 Research support was provided by Diyar Barzanji, Frauke Maas, and Hana Nasser.

2 Reports indicate that following the ISIL assault, thousands of non-Muslims across the Ninewa Plains were killed, about 5,000 Yazidi women were captured and held as sex slaves, and 500,000 Yazidi minorities were subsequently displaced. Jeremy P. Barker, “A Flicker of Hope? Implications of the Genocide Designation for Religious Minorities in Iraq,” Religious Freedom Institute, July 30, 2016, www.religiousfreedominstitute.org/cornerstone/2016/7/30/a‑flicker-of-hope-implications-of-the-genocide-designation-for-religious-minorities-in-iraq.

3 Ibid.

4 ISIL’s abuse of religious minorities in Iraq, including the Christians in Qaraqosh, has been declared an act of genocide by the European Parliament, the United States, the United Kingdom, and other international authorities. Jack Moore, “European Parliament Recognizes ISIS Killing of Religious Minorities as Genocide,” Newsweek, February 4, 2016, http://www.newsweek.com/european-parliament-recognizes-isis-killing-religious-minorities-genocide-423008; European Parliament, Resolution 2529, “European Parliament Resolution on the Systematic Mass Murder of Religious Minorities by the So-called ‘ISIS/Daesh’,” February 3, 2016, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-%2f%2fEP%2f%2fNONSGML%2bMOTION%2bP8-RC-2016 – 0149%2b0%2bDOC%2bPDF%2bV0%2f%2fEN; Andrea Mitchell, Cassandra Vinograd, F. Brinley Bruton, and Abigail Williams, “Kerry: ISIS is Committing Genocide against Yazidis, Christians and Shiite Muslims,” NBC News, March 17, 2016, http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/isis-terror/kerry-designate-isis-atrocities-genocide-n540706.

5 UN Habitat, UN Habitat, Multi-Sector Assessment of Mosul, Iraq (Baghdad: United Nations Human Settlements Programme in Iraq, 2016), 14, reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UN-Habitat_MosulCityProfile_V5.pdf. The map notes that the figures are based on 2009 population figures.

6 They are often simply referred to as “Christians” which some of them feel disregards the ethnic aspect of their identity; however, for the sake of brevity, this research summary will generally refer to the Christian populations without further denominational divisions. Maxim Edwards, “Ethnic Dimensions of Iraqi Assyrians Often Ignored,” Al-Monitor, October 10, 2014, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2014/10/iraq-assyrians-ethnic-rights-ignored.html.

7 The Shabak minority, numbering between 250,000 and 400,000, are predominately Shi’a, though a small amount are also Sunni. They reside almost exclusively in the Ninewa Plains area. Due to their geographic location, they have historically faced discrimination from both Arabs and Kurds. Mina al-Lami, “Iraq: The Minorities of Nineveh Plain,” Assyrian International News Agency, July 21, 2014, http://www.aina.org/news/20140721084628.htm.

8 Although a small minority, the Shabak are an important potential wedge group in the Baghdad-KRG competition for the Disputed Territories because of the different perceptions (internally and externally) of their ethnic and sectarian origins. Kurds tend to assume that the Shabak are ethnic Kurds, which some Shabak also identify with. However, many other Shabak claim a distinct ethnic identity but religiously identify themselves as Shi’a. More recently in the post-2014 period and in the years leading up to it, significant portions of the Shabak community have chosen to align with Shi’a Arabs.

9 Sean Kane, Iraq’s Disputed Territories (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, 2011), 18, www.usip.org/publications/2011/04/iraqs-disputed-territories.

10 Ibid.

11 A political representative of the NPGF, Khalid Ayshoa Esttaifo, noted in an interview for this study that the NPGF was championed from the beginning by Sarkis Aghajan Mamendo, an Assyrian member of the KDP who served as KRG Finance and Economy Minister from 1999 to October 2009 and as Deputy Prime Minister from 2004 to 2006. It was not clear if initial financial support for the guards force came from Mamendo himself, KRG offers, or a combination of both, but the NPGF was certainly sanctioned by the KRG.

12 “Peshmerga Fight ISIS in Nineveh; Militants an Hour Away from Baghdad,” Rudaw, June 26, 2014, http://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/260620141.

13 “Iraq Christians Flee as Islamic State Takes Qaraqosh,” BBC News, August 7, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-28686998.

14 Samuel Smith, “ISIS to Crucified Christians: ‘If You Love Jesus, You Will Die Like Jesus’,” Christian Post, November 28, 2016, http://www.christianpost.com/news/isis-told-crucified-christians-if-you-love-jesus-you-will-die-like-jesus-171766/; Human Rights Watch, Iraq: ISIS Abducting, Killing, Expelling Minorities (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2014), https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/07/19/iraq-isis-abducting-killing-expelling-minorities.

15 Smith, “ISIS to Crucified Christians”; Nina Shea, “The Islamic State’s Christian and Yizidi Sex Slaves,” Hudson Institute, July 31, 2015, https://www.hudson.org/research/11486-the-islamic-state-s-christian-and-yizidi-sex-slaves; Eliza Griswold, “Is This the End of Christianity in the Middle East?” New York Times, July 22, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/26/magazine/is-this-the-end-of-christianity-in-the-middle-east.html?_r=0.

16 Shea, “The Islamic State’s Christian”; “SRSG Bangura and SRSG Mladenov Gravely Concerned by Reports of Sexual Violence against Internally Displaced Persons,” United Nations Iraq, August 12, 2014, http://www.uniraq.org/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=2373:srsg-bangura-and-srsg-mladenov-gravely-concerned-by-reports-of-sexual-violence-against-internally-displaced-persons&Itemid=605&lang=en.

17 Nineveh Reconstruction Committee, “The Challenges are Enormous,” Aid for the Church in Need, May 11, 2017, www.nrciraq.org/nineveh-plains-destruction-images/.

18 Andrew Doran, “Fighting for the Ruins of Christian Iraq,” CNN, June 29, 2015, http://edition.cnn.com/2015/06/29/world/christian-iraq-doran/index.html.

19 Paul Torpey, Pablo Gutiérrez, and Paul Scruton, “The Battle for Mosul in Maps,” The Guardian, June 26, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/04/battle-for-mosul-maps-visual-guide-fighting-iraq-isis; Josie Ensor, “Near Mosul, Church Bells Ring out in a Christian Town Freed from Terror,” Telegraph, October 22, 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/22/near-mosul-church-bells-ring-out-in-a-christian-town-freed-from/.

20 “Mosul Offensive Day 22: Peshmerga Liberate Bashiqa,” Rudaw, November 7, 2016, http://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/07112016.

21 Nineveh Reconstruction Committee, “Qaraqosh/Bakhdida Restoration Process and Returnees,” Aid for the Church in Need, 2017, https://www.nrciraq.org/reconstruction-process/karakosh-bakhdida-restoration-process-and-returnees/.

22 For more see, “Freed from ISIS, but Iraq’s Qaraqosh Is Now a Ghost Town,” Al Arabiya English, March 29, 2017, english.alarabiya.net/en/features/2017/03/29/Freed-from-ISIS-but-Iraq-s-Qaraqosh-is-now-a-ghost-town.html.

23 For a more detailed description of the different forces that have emerged within the Yezidi community and how these forces have become enmeshed in different regional and national proxy contests (not dissimilar to the Christian militias), see Christine van den Toorn and Sarah Mathieu-Comtois, Sinjar after ISIS: Returning to Disputed Territory (Utrecht: PAX for Peace, 2016).

24 Matt Cetti-Roberts, “Inside the Christian Militias Defending the Ninevah Plains,” War is Boring. Blog post. March 7, 2015. medium.com/war-is-boring/inside-the-christian-militias-defending-the-nineveh-plains-fe4a10babeed.

25 Based on interviews with NPF representatives, members of the KTCC, and diplomatic officials involved with the Coalition, the NPF have received training as part of the Peshmerga through the KTCC, which is the Peshmerga training program supported by nine coalition members, including Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Hungary, among other nations.

26 Michael Knights and Yousif Kalian, Confidence- and Security-Building Measures in the Nineveh Plains (Washington, DC: The Washington Institute, 2017), www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/confidence-and-security-building-measures-in-the-nineveh-plains.

27 “Christians Reclaim Iraq Village from ISIS,” CBS News, November 13, 2014, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/christian-iraq-village-kurdish-peshmerga-fighters-bakufa-isis/; Cetti-Roberts, “Inside the Christian Militias.” Reports indicate that two Americans, and eight foreigners, in total, have joined the militia; Peter Henderson, “Iraq’s Christian Paramilitaries Split in IS Fight,” Al Monitor, October 30, 2014, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2014/10/iraq-christian-paramilitary-forces-nineveh.html; Rebecca Collard, “Meet the Americans Who Have Joined an Iraqi Militia to Fight ISIS,” Time, March 27, 2015, http://time.com/3761211/isis-americans-iraqi-militias/.

28 The United States, for example, has allocated funding for Christian militias in the Ninewa Plains. The U.S. Defense Appropriations Act for fiscal year 2018, H.R. 2810, which at the time of research had passed the House but was awaiting Senate action, allocates funding to “vetted” Christian militias in the Nineveh Plains Council. National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018, H.R. 2810, 115th Cong. (2017), 612. Last year, Senate Bill 2943, authorizing DOD funds for fiscal year 2017, had also stated that providing security for Christian minorities in the Ninewa Plains was a defense priority for the United States. National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017, S. 2943, (2016), 614.

29 The group was politically sponsored (i.e. put forward for PMF membership) by the Shabak politician and Member of Parliament Hunain Qaddo, and Wat Qaddo is the tactical commander in charge of the 30th Brigade.

30 Numerous interviewees from all sides, including Christian political representatives, foreign diplomatic personnel, and Iraqi military leadership, warned that the Babylon Brigades’ propensity for revenge attacks and abuses against Sunnis in their area of operations risked instigating further cycles of violence and conflict. One coalition official interviewed in July 2017 noted that Babylon Brigades had reached such a level that both the Iraqi National Security Service (NSS) and PMF leadership were trying to reign in the Babylon Brigades because they were getting “out of control.”

31 As Yakoub explained, Christians knew that they did not have sufficient forces to liberate their areas on their own: “We thought we cannot liberate them without any force or military. But we must share the burden with others, either military forces in Baghdad or the Ministry of Peshmerga.”

32 Allegations that Shabak PMF may have been involved in looting and damage in Qaraqosh and surrounding areas immediately after it was recaptured was alleged by several interviewees and has been mentioned in other human rights reporting. Human Rights Watch, Looting, Destruction by Forces Fighting ISIS; No Apparent Military Necessity for Home Demolitions (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2016), https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/02/16/iraq-looting-destruction-forces-fighting-isis.

33 Many former residents from Christian areas in the Ninewa Plains have resettled in Erbil’s large Christian area. Humanitarian actors interviewed said that they frequently suggest they would not return, or at least not yet, because their families are integrated into the Erbil community, with children enrolled in local schools and families engaged in local employment in Erbil.

34 This concern was notably suggested by Haitham al-Mayahi, director of the PMF media office for Mosul operations and political advisor to Hadi al-Ameri, in a December 2016 interview for this study. He recommended that it would be better for the Babylon Brigades to take control of Hamdaniya, rather than other forces, because of their local status. While this view is only one among many, if leading spokespersons of the powerful Badr Organization are suggesting that the Shabak militias be given control of Hamdaniya, then perhaps Christian fears of a Shabak takeover are not without basis.

35 A representative from the NPGF pointed out in an interview that they have a much greater number of forces, have been longer-standing, and have more training and support; therefore, they would be better suited to contributing to demining and other security tasks in Qaraqosh. The NPU representatives interviewed in Qaraqosh said they had sufficient levels of staff for the necessary security and patrol duties and were already engaged in demining and some reconstruction activities. Several civilian IDPs interviewed offered the opinion that none of the Christian forces was strong enough to guarantee security in Hamdaniya, given the strength of other forces and continuing risk of Christian persecution by ISIL.

36 For a further example of such claims for autonomy, see Marco Gombacci, “Iraqi Christians Ask EU to Support the Creation of a Nineveh Plain Province,” European Post, March 14, 2017, http://europeanpost.co/iraqi-christians-ask-eu-to-support-the-creation-of-a-nineveh-plain-province/.